Specific Violations of Law and Regulation, by Major Issue.Protecting and increasing Old Growth forests.Violations: NFMA 219.1(a) and 219.4(a)(2) Maximize net public benefits; 219.1(b)(13) Sensitive to economic efficiency; 219.27(a)(12) Maintain air quality; NEPA 1500.1(b) Information must be of high quality; 1500.2(f) Quality of human environment; 1502.24 Insure professional integrity; APA Section 706(2)(A) Arbitrary and capricious. The first purpose given for the change in Regional direction is "Protect, increase, and perpetuate old forest ecosystems and provide for the viability of native plant and animal species associated with old forest ecosystems." [ROD pg 1] The desired future conditions that are given for achieving this goal include "The density of old trees and the continuity and distribution of old forests across the landscape is increased. The amount of forest with late-successional characteristics ... is also increased." [ROD pg 8] In direct contradiction to its statements of purpose and desired future condition, the Decision would result in significantly less density of old trees and continuity and distribution of old forests across the landscape than would be provided by one or more of the alternatives rejected. The FEIS and the planning record themselves include three graphs that provide evidence that other alternatives would be significantly better in protecting old trees and sustaining late-successional characteristics: "Projected number of large trees" [Appeal Appendix B, pg 6]; "Projected number of very large trees greater than 50 inches in diameter" [Figure 3.1h, FEIS Vol 2, Ch 3, pg 89, and Appeal Appendix B, pg 7]; and "Projected late seral stage forest acres" [Figure 3.1 i, FEIS Vol 2, Ch 3, pg 90, and Appeal Appendix B, pg 4]. Whether one takes the short view or a longer view, these three graphs are sufficient to establish at least that alternative 8-mod is not a viable candidate for preferred alternative. Short run considerations. NFMA sets the maximum life span of a Forest Plan at 15 years. According to the three tables listed above, there is no statistically significant difference within two decades among the alternatives in projections of large trees or very large trees, and if there is a significant difference regarding late seral stage forest within the first two decades, it is that alt 8-mod is already below all other action alternatives. Thus it is not possible to make a logical choice of 8-mod among alternatives in their supposed effect on these key elements of "old growth forest" within the expected lifetime of the adopted alternative. Yet it appears the main reason given for choosing Alt 8-mod was its supposed superiority in preserving and enhancing old growth forest characteristics, as represented by large trees, very large trees, and late seral stage forest. In effect the Forest Service has chosen to do away with the timber and biomass power industries in pursuit of an advantage their own analysis shows cannot be achieved by the adopted alternative but possibly could be achieved by one of the other alternatives that was considered but not adopted.. Long run considerations. If one takes the view that long term projections should be accepted as evidence for the potential success of an old growth enhancement strategy, then all three graphs do show that significant trends in large trees and very large trees become apparent in about the fifth decade and continue through the whole 14-decade analysis period, with Alt 8-mod always below the average of all other action alternatives. On the later seral stage graph, Alt 8-mod starts at the bottom of all action alternatives and stays there, falling farther short of average all along the way.

|

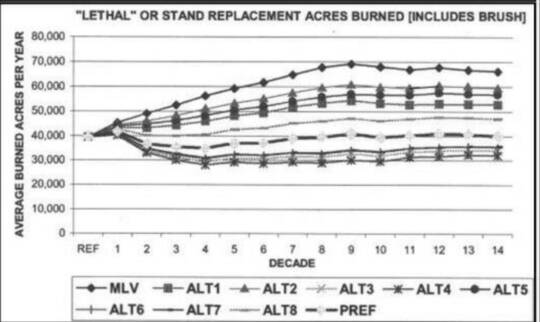

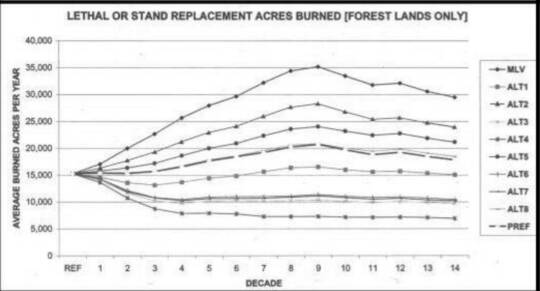

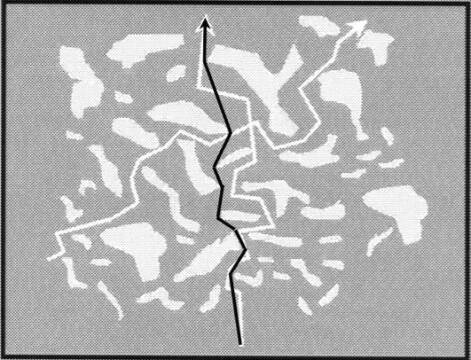

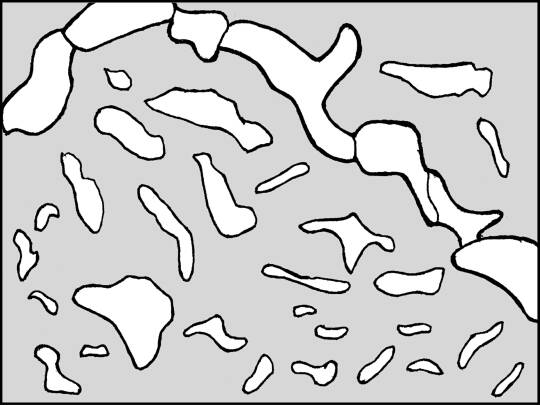

Effect of Wildfire. A major reason for the poor performance of Alt 8-mod on large trees, very large trees, and late seral forest, is that it also does poorly on wildfire losses. The FEIS provides only a graph for "Acres projected to burn by wild fires based on SPECTRUM model estimates" [Figure 3.1 e, FEIS Vol 2, Ch3, pg 85, and Appeal Appendix B-2, pg 1]. On this graph Alt 8-mod is again in the middle of the pack, with four of the other action alternatives consistently better and three of them worse. The FEIS also includes a graph "'Lethal' or stand replacement acres burned [includes brush]" [Figure 3.5 u, FEIS Vol 2, Ch 3, pg 293], which again shows Alt 8-mod about in the middle of other action alternatives. However, this graph does not reveal the full significance of Alt 8-mod's poor performance regarding lethal fire effects on old growth forest. A graph for "Lethal or stand replacement acres burned [forest land only]" is in the planning record [Appeal Appendix B, pg 2] which was not published in the FEIS. These two graphs, one from the FEIS including "lethal or stand replacing brush fire," and the other "forest only," are reproduced below.

|

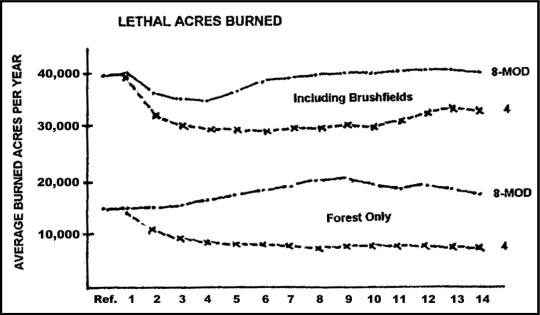

It is difficult to see the significant differences in these two graphs, because they are cluttered with numerous lines and they have different vertical scales. Therefore we have combined the two graphs below, showing "with brush" and "forest only" at the same scale, and retaining only Alt 8-mod and Alt 4 (because Alt 4 performed best on this measure).

Several things become much more clear in this comparison, where the same scale was used for both "with brushfields" and "forest only." (1) The apparent dip in lethal fire acres under Alt 8-mod in the early decades is entirely due to burning more brush, not reducing the amount of lethal forest fire acres. (2) The amount of brush burned (i.e. the distance from one line to the other for either alternative) is relatively constant for both alternatives across the whole analysis period. This indicates that including "brush" in the FEIS graph served mainly to obscure the real differences among alternatives on this vital measure of treatment effectiveness. (3) The inclusion of brush acres in the FEIS graph causes the percentage advantage of Alt 4 over Alt 8-mod to seem less than the difference between them regarding forest alone. That is, in the "with brush" graph Alt 4 appears on average to be only about 20 percent better than Alt 8-mod, whereas on the unpublished "forest only" graph Alt 4 is more like 60 percent better. Most people would also question the implicit assumption in the FEIS graph that killing large green trees with fire is no different from killing brush with fire. In many circumstances the killing of brush would be an advantage, not a detriment to forest management. Other wildfire considerations. The above direct evidence is strongly supported by indirect evidence in the FEIS that Alternative 8-mod is notably inferior to one or more other alternatives in achieving the desired future condition that supposedly motivates and justifies the Decision. In its discussion of "Estimating Fire Effects" the FEIS [Vol 2, Ch 3, pg 278] includes the passage quoted below, which has particular relevance to the hazard of wildfire to old trees and late seral conditions.

|

After discussing the relationship of flame length and scorch height to mortality in the relatively benign conditions assumed to be present when prescribed fire is used, the FEIS continues: ... The calculated value for scorch height varies only slightly between 40 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit and 0 to 10 mph mid-flame windspeeds. These conditions are applicable for many prescribed fires. Under wildland fire conditions, where temperatures and windspeeds are often much higher, mortality is often under predicted, especially large tree mortality. FOFEM outputs were part of each prescription in the SPECTRUM modeling for each alternative. The majority of large tree (greater than 30 inches in diameter) mortality accounted for in SPECTRUM is from fire. (emphasis added) In other words, the survival of large trees, and thus the long term viability of wildlife that depends on old forest habitat, is at greatest risk from wildfire, and the graphs referred to above under-predict such mortality, especially in the large trees. Since the under-prediction would be most significant in the alternatives that show the greatest amount of wildfire, the deficiency of Alternative 8-mod in assuring long term sustainability of old forest conditions is even more serious than the FEIS graphs would indicate, and those graphs already show an unacceptable deficiency in Alternative 8-mod. When the unpublished graph of lethal wildfire on forest acres only is factored in, the evidence showing poor performance by Alt 8-mod is overwhelming. The FEIS discussion of fire effects [Vol 2, Ch3, pg 278] also highlights the fact that, under the assumptions and restrictions imposed by Alternative 8-mod, fuel reduction treatments probably cannot be implemented effectively and to the extent proposed in the Decision. The SPECTRUM modeling did not place constraints on amounts of smoke emissions and budget allocations, nor did it impose limited operating periods for scheduling treatments. Any of these constraints could reduce or limit the actual number of acres treated under the alternatives. Compared to one or more of the alternatives that would permit greater reductions in wildfire acres and show higher survival of late seral acreage, Alternative 8-mod would have a greater net cost (considering cost of treatments, fire losses, and federal revenue yields), generate more smoke, and impose more restrictive Limited Operating Periods. Finally, Alternative 8-mod depends entirely on the SPLAT strategy for fuel reduction in threat, old forest emphasis, sensitive wildlife habitat, and general forest areas. As we discuss later in this appeal, the SPLAT strategy would not and could not provide the level of protection claimed for it. Therefore, actual mortality of large trees and old growth forest structures would be even worse than the already unacceptable results revealed by the projections published in the FEIS and buried elsewhere in the planning record.

|